March 21, 2019 – When Jessie Diggins crossed the finish line first in the women’s Team sprint competition at Pyeongchang, South Korea on Feb. 21, 2018, winning historic Olympic gold with her teammate Kikkan Randall, more than five decades of American women who had donned international race bibs stood up and cheered, along with countless other Nordic fans. The pair had just achieved a spectacular all-time best result, capturing the first Olympic medal in the history of U.S. women’s cross-country skiing.

![American Jessie Diggins (l) outsprints Sweden’s Stina Nilsson by a scant 0.19 seconds in the women’s Team Sprint at Pyeongchang 2018, claiming the U.S.A.’s first Olympic gold medal in cross-country skiing with teammate Kikkan Randall [P] Nordic Focus](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Diggins-Pyeongchang-21022018fm0061_EXT-525x337.jpg)

For others, it was a male friend who was racing cross-country who got them going. Trina Hosmer remembers, “I started skiing when I went to UVM in 1966 and met Dave [her husband]. He was captain of the men’s ski team (as yet, no women’s team existed), and he encouraged me to start cross-country skiing. So I would tag along with the rest of the team, who were all very supportive and encouraged me to keep at it.”

Sara Mae Berman had the support and encouragement of her husband, Larry – both had a background in running. As they watched the 1964 Winter Olympics on television, they heard the Nordic commentator note, “There are no American women in this event.” At that point, Berman turned to his wife, challenging her while also assuring her that she was tough enough to take on this winter sport. She remembers, “That’s when we both began to learn what was involved in cross-country skiing. We ordered racing equipment from the only Nordic ski store in Boston, entered a race from a flyer that Larry saw on the store wall and bought John Caldwell’s book.”

And there were coaches with cross-country programs who invited and welcomed participation by females. Herb Thomas was a four-way ski competitor at Middlebury College. He returned to his hometown of Wenatchee, Wash. and started up a ski club for juniors, which he advertised in the local newspaper. The Owen family saw the ad and decided to give it a try with Alison joining her four brothers and immediately loving it. “It didn’t bother me that other girls didn’t do it; I was used to being the only girl hiking and adventuring with my family,” she recalled.In Alaska back in 1962, Jim Mahaffey, who had skied at Western State in Colorado, took over the fledgling ski team at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks (UAF), and had two or three girls skiing on his team. That next year, the first intercollegiate ski meet in Alaska was held between UAF and Alaska Methodist University (AMU). The UAF women raced despite not having any female counterparts yet from AMU. Mahaffey shared his memories of the cross-country-ski scene in Alaska in the early 1960s. “There was a lot of Nordic ski activity happening at the time in Alaskan high schools for both boys and girls. Parents recognized the value of participation in cross-country and supported it; high schools included it in their physical-education classes, as well as having competitive teams. The Nordic Ski Club of Anchorage was begun and developed a solid membership,” he recalled.

The mid-1960s saw the beginning of significant advances for women’s cross-country skiing in the U.S. At the 1966 Nordic World Championships in Oslo, Norway, where a U.S. men’s team was competing, team manager Bob Tucker and coach John Caldwell met with Swedish International Ski Federation (FIS) representative Inga Lowdin. Lowdin was interested in helping to grow the sport for women, and agreed to send three top Swedish women the following winter to the U.S. to promote cross-country with a series of clinics while competing at races.

![Alison Owen won the first women’s FIS XC Ski World Cup race at Telemaek, WI in December 1978 [P] Hall Collection](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/World-Cup-1978-copy-525x419.jpg)

![Bob Tucker in 1967 with Swedish ladies team: (l-r) Barbo Martinsson, Aase Kaarlander and Toni Gustafsson [P] Tucker Collection](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Bob-Swedish-XC-Members-6-copy-525x359.jpg)

The Scandinavians continued their tour across the U.S., including stops in Wenatchee and Fairbanks. Alison Owen joined the Swedes during their visit and was inspired when she saw them beat all the U.S. collegiate men except for John Bower. “Skiing is in my blood . . . I was born to ski,” she recalled of those heady days when she was raring to go.

Junior National races for girls were held for the first time in Duluth, Minn. in March 1967. Mahaffey brought a strong contingent of skiers down from Alaska; other girls came on teams representing the Eastern, Central, Intermountain, Northern and the Pacific Northwest divisions. With solid high-school programs in place, the Alaskan girls captured the four-team relay race title ahead of the Eastern and Intermountain squads, then swept the podium in the 5km Individual, with Barbara Britch winning, Sharon Strutz placing second and Janie Whitmore placing third.

The following winter, the number of girls racing at the Junior Nationals grew from the previous 17 to 31. Canadian skiers joined the event and showed their strength, with Shirley Firth winning the 4km, her sister, Sharon, placing third, and Britch sandwiched between the two in second. That spring, in 1968, the first U.S. women’s cross-country National team was named by U.S. Nordic program director Al Merrill: Berman of Massachusetts, Britch and Strutz of Alaska, Trudy Owen of Wyoming and Mary Pendleton of Vermont.

Legendary U.S. coach Marty Hall was tapped by Merrill to lead this women’s team and provide them with a program. “For me, the spark that led to the formation of the first U.S. women’s cross-country team was Alison Owen from Wenatchee, who had no one to race against at the Junior Nationals the previous year – she raced with the boys,” said Hall. “Al Merrill and I sat down and laid out the framework and it was my mandate to make it happen. My wife, Kathy, and I created a points system for criteria that is still used to this day. There were try-outs and the first team was formed with Alison Owen, Martha Rockwell, Trina Hosmer and others joining later”Britch, Pendleton and Alison Owen, all junior skiers, were given the opportunity during Christmas of 1968 to race in Sweden. Britch won one race and finished second in another. She went on to race in the European Junior Championships and earned a 15th-place result. Back in the U.S., Rockwell claimed two of her 18 career National Championship titles, ahead of young Colorado skier Kris Zdechlik.

The 1970 World Nordic Championships were held in Vysoke-Tatry, Czechoslovakia in February. The U.S. women’s team was chosen based on tryout races in Lake Placid and Putney in January. Hosmer, Rockwell, Britch and Alison Owen qualified. Hall led them as the coach and Gloria Chadwick accompanied the group as chaperone. In this, their first attendance at the Nordic World Championships, the U.S. women’s placements ranged from 25th to 43rd in the 5km, and 28th to 36th in the 10km, with a remarkable 11th in the relay.This group of pioneers put down the first stepping stones for future women skiers to follow. It was not an easy path; at times it was “really rough,” as Rockwell put it. After having skied in the 1970 World Championships, Britch stepped down from the U.S. team because of economic reasons – there was no sponsorship or athletic funding for her despite her being one of America’s top skiers. Also lacking were organized cross-country programs if one was outside of school. Britch went back to work in her hometown of Anchorage, Alaska, continuing to ski on her own.

![1972 – First Womens OFirst U.S. women’s Olympic team for the 1972 Games in Sapporo, Japan (l-r) Marty Hall (coach), Barbara Chadwick (chaperone), Trina Hosmer, Margie Mahoney, Barbara Britch, Alison Owen [P] Hall Collection](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/1972-First-Womens-Olympic-XC-Ski-Team-copy-copy-525x420.jpg)

In 1974, she earned 10th in the 10km at the World Championship in Falun, Sweden despite a late-race collision with a course official who was mistakenly in her path. The collision cost her four places, dropping her from sixth prior to the last downhill into the stadium. “They apologized profusely and the organizers came by during dinner and apologized yet again,” remembered Hall. “It was a tough pill to swallow, but there was nothing anyone could do.”

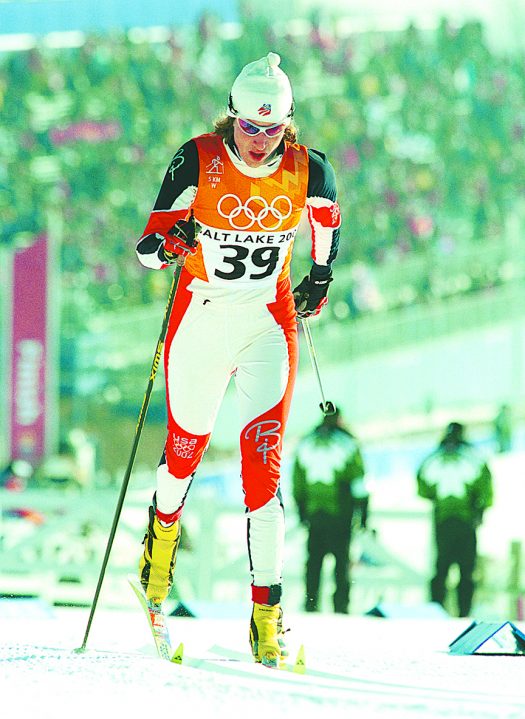

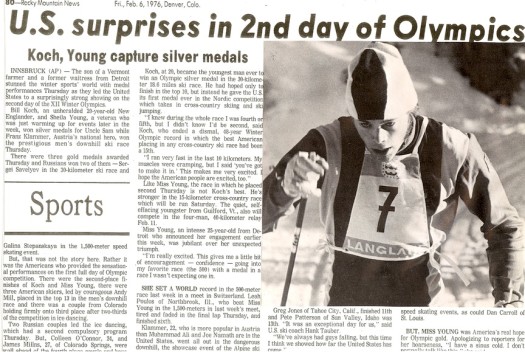

The following season, Rockwell won five of the six European races she competed in, landing 10th overall in the FIS cross-country standings. Then, in 1976, the Winter Olympics were held in Innsbruck, Austria. Along with Rockwell was 1972 teammate Mahoney, as well as four new Olympians: Twila Hinkle, Jana Hlavaty, Terry Porter and Lynn Spencer-Galanes. Rockwell led the U.S. women with her 28th in the 5km and 36th in the 10km.

Soviet skier Galina Kulakova placed third in the 5km, but was later disqualified when doping control revealed traces of ephedrine, reportedly from a nasal spray. It was the first doping positive in Olympic cross-country skiing. Kulakova had won three cross-country gold medals during the 1972 Winter Olympics four years prior.

Still, the 1976 Games at Innsbruck were historic, as American Bill Koch stunned the world, capturing the U.S.A.’s first Olympic medal, winning silver in the men’s 30km Classic – Hall was the Team USA head coach at those Games.The decade of the 1970s closed out with Alison Owen earning top international placements. In December 1978, she won the first women’s FIS World Cup race in Telemark, Wis. With many top-10 international placements, she finished out the 1979 season with an amazing World Cup ranking of seventh. After the Olympics in Lake Placid, N.Y., she stood upon the podium at Oslo, Norway’s famed Holmenkollen, having skied to an incredible second place in the 10km race in March.

Yet attaining these same top placements at the Nordic World Championship and Olympic competitions seemed to elude the U.S. skiers. At the 1980 Olympics in Lake Placid, Alison Owen had the highest placements for the American women, with her 22nd-place result in both 5km and 10km competitions.

The number of U.S. women invested in cross-country skiing, training year-round and pursuing high-level competitive goals had grown significantly by the 1980s. The sport of cross-country skiing itself had gained popularity, and support, programs and competitions for women multiplied. Most of the programs with coaching were supplied through educational institutions, private and public high schools, and colleges and universities.

The women’s field at the 1982 National Championships saw 55 athletes invited to compete. The women’s race at the Williams College Carnival, one of the popular Eastern collegiate race weekends, had 40 competitors from nine teams in New England, including those from such universities and colleges as New Hampshire, Vermont, St. Lawrence, Bates, Bowdoin, Dartmouth, Middlebury, New England and Williams. Colleges and universities in the Midwest, West and Alaska attracted and developed talented women skiers. At least one ski academy, Stratton Mountain School, originally created for alpine skiers, added a Nordic program as well.

The U.S. Ski Team (USST) annually named a small group of skiers based on the previous season’s results, for whom it provided coaching, training camps, competition trips, waxing, equipment assistance through a supplier pool, and uniforms. Non-team skiers could earn their way to World Cup, World Championship and Olympic events by faring well in tryout races. While there was a small core of U.S. skiers who competed internationally throughout the entire winter season, there were others who would get their one trip overseas for several weeks and then return to the domestic races for the rest of their season.

In those years with few non-school programs available, departure from the National team’s umbrella of support often meant that skiers were now on their own. Overseas, the Norwegian women came on strong in the 1980s and challenged the historically strong Soviet women for top spots, while individuals from Czechoslovakia, Finland, East and West Germany, Sweden and Switzerland also broke through with podiums and top-10 results.

For the Americans, top-20 placements were cause for celebration. In 1983, Judy Rabinowitz had several 16th-place finishes in World Cup races. A ninth at the Anchorage World Cup event landed her 20th overall at season’s end.![U.S. women’s team in 1992 (l-r) Nancy Fiddler, Betsy Youngman, Dorcas DenHartog, Leslie Thompson and Ingrid Butts [P] Thompson Collection](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/W-XC-Ski-Team-USA-00040025.2-copy-525x343.jpg)

The top Olympic women’s relay placements were achieved in Lake Placid and Sarajevo, with both teams earning seventh-place results. The final Winter Olympics of the 20th century was held in Nagano, Japan. Laura Wilson earned the top placing for the Americans with her 36th in the 30km.

The FIS Nordic World Championships were equally challenging. In 1985 at the first World Championships where most competitors raced without kick wax, Sue Long, using the new skating technique, finished 17th in the 20km, the top American result in Seefeld, Austria. In 1989, Fiddler earned a 15th place in the 15km Classic race at the World Championships in Lahti, Finland. Leslie Thompson earned 20th in the 30km at the 1993 Worlds in Falun, Sweden.

![At the 2002 Olympics in Salt Lake City, Canada’s Beckie Scott celebrates breakthrough bronze which became silver and finally gold [P] Heinz Ruckemann](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Beckie3_OLY1502-copy-525x748.jpg)

“Beckie’s medal in 2002 definitely had a big effect on me. As a fellow North American, when I saw her succeed it made me feel like there was no reason that I couldn’t do it. It made me want to get a women’s medal for the U.S., just like she did for Canada,” recalled Randall. “I think it was also inspiring to me that it took her many years to reach the top level. It gave me confidence that if I just stayed on track, I would get there too someday. The whole women’s cross-country team from Canada around those 2002 Olympics was inspiring, all the way up through 2006.”

![Canadian Chandra Crawford, 22, won gold in the Individual freestyle sprint at the Torino Games in 2006 [P] Heinz Ruckemann](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/CHANDRA.Torino.44-copy-525x464.jpg)

Apparently competing at the Games runs in the family, as Betsy and Chris Haines, Randall’s aunt and uncle, both raced in Olympic cross-country-ski races.

Following the 2006 Games, the USST made some big changes. Randall was named to the “A” team and a large development team was established. The development team, with Pete Vordenburg as coach, included Liz Stephen and Morgan Arritola, both of whom moved to Park City, Utah to train with USST coaches; three athletes, Lindsay Williams, Lindsay Weier and Morgan Smyth, from Sten Fjeldheim’s Northern Michigan University team; and Tazlina Mannix with Alaska Pacific University’s cross-country ski program.

This new commitment to women’s skiing was notable, as in the previous year, absolutely no women had been named to be part of the National team with its five men. That year, Chris Grover became the USST sprint coach and Matt Whitcomb was tapped to be the head development coach.

![Kikkan Randall sets the best-ever American women’s Games result at Torino in 2006, finishing 9th the freestyle Sprint [P] Heinz Ruckemann](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Randall_Torino_2006_05.4-516x760-copy-516x760.jpg)

Stephen gained the first medal for the American women in a World Championship race, claiming bronze in the 15km freestyle at the 2008 U23 Nordic World Championships. Sadie Bjornsen, Rosie Brennan, Ida Sargent, Sophie Caldwell and Alexa Turzian made up the U.S. contingent of racers at the Junior World Championships that season, picking up valuable international experience.

With these international podium achievements, the appetite grew for more. Randall won her first FIS Nordic World Championship medal, a silver, in the freestyle sprint in Liberec, Czech Republic in 2009. She was joined by Stephen, Arritola, Caitlin Compton and APU-coach-turned-winning competitor Holly Brooks on the 2010 Olympic team. A combination of seeing the U.S. Nordic-combined squad capture four medals and Randall’s experience in the 4x5km relay, during which she led for a time on the starting leg, increased her belief that American skiers could successfully compete with the world’s best.At season’s end, Grover stepped into the head-coach spot vacated by Vordenburg, and Whitcomb became head coach of women’s team. Building a true team that supported each other and enjoyed their time together became a priority for the women and their coach.

![Kikkan Randall (l) and Sadie Bjornsen win silver – the U.S.A.’s first Team Sprint medal [P] Nordic Focus](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Randall-Bjornsen-041211ah205-copy-525x441.jpg)

The first women’s-only training camp was held in Alaska during the summer of 2011. That next December, Randall won the Individual World Cup sprint in Dusseldorf, Germany. For the first time in that city event, Randall had a partner for the Team sprint the following day – Bjornsen.

The two captured silver, the first Team sprint podium for the U.S. women. Weeks later, Diggins, who also joined the team that season, paired up with Randall and claimed another Team sprint silver in Milan, Italy. The now famous red-white-and-blue relay socks purchased at a convenience store in Germany by Randall made their World Cup debut in Milan, Italy.

With her season of five World Cup podiums including two wins, Randall earned the overall Sprint World Cup title in 2012, a historic first in U.S. women’s racing.

The 2012-13 winter season started off with a bang for the American women. The relay team of Brooks, Randall, Stephen and Diggins took home the American women’s first World Cup relay podium, placing third at Gallivare, Sweden in November. The circuit moved across the Atlantic to Quebec City, Canada, and Diggins and Randall teamed up to win the first World Cup team sprint for the U.S.A.

![U.S. women’s relay team and their famous socks (l-r) Kikkan Randall, Sadie Bjornsen, Jessica Diggins, Elizabeth Stephen [P] Nordic Focus](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/W-Relay-Team-USA-081213al007.4-copy-525x400.jpg)

![Jessie Diggins and Kikkan Randall combined to win America’s first-ever FIS Nordic World Championship gold in the Team sprint at Val di Fiemme, Italy in 2013 [P] Nordic Focus](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Diggins-Randall-Jump-240213al102-copy-525x350.jpg)

![Legendary Kikkan Randall celebrates her third Sprint Cup globe and an incredible career of historic results and inspirational passion with her teammates [P] Nordic Focus](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Randall140314mf151-copy-525x350.jpg)

Six weeks later, with Caldwell skiing the first leg, they nailed a team-best silver in Nove Mesto, Czech Republic. At the World Championships, new medals were earned: Diggins and Caitlin Gregg won silver and bronze in the 10km freestyle in Falun, Sweden in 2015, Diggins and Randall earned silver and bronze in the freestyle sprint and Bjornsen and Diggins captured bronze in the Classic Team sprint in Lahti, Finland in 2017.

By the start of the 2018 season, six different women had stood on a World Cup podium: Sargent, Stephen, Bjornsen, Caldwell, Diggins and Randall. Caldwell and Diggins had joined Randall in the elite group who have stood on the top step as the winner of a World Cup race.

![Team USA celebrates Jessie Diggins and Kikkan Randall’s historic first Olympic gold medal in cross-country skiing at Pyeongchang 2018 [P] Steve Fuller](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Olympic_20180221_SprintRelay_66820-Edit-ST-copy-525x350.jpg)

In the very first cross-country race of the Games, Diggins earned a U.S. best-ever with her fifth in the 15km Skiathlon. She followed that up with sixth in the Classic sprint and fifth in the 10km freestyle. The 4x5km relay team of Caldwell, Bjornsen, Randall and Diggins took home an Olympic relay best of fifth. Their results were oh-so-tantalizingly close to attaining the long-sought-after Olympic hardware.

![Kikkan Randall and Jessie Diggins with legendary Bill Koch who won silver in the men’s 30km Classic at the 1976 Games in Innsbruck, the U.S.A.’s first Olympic medal [P] Reese Brown](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Randall-Koch-Diggins-Super-Tour-Finals-2018-10K-15K-3.24.18-1353-XL-copy-525x349.jpg)

![The U.S.A.’s Jessie Diggins (l) and teammate Kikkan Randall at the finish of the women’s Team Sprint at Pyeongchang 2018, claiming the U.S.A.’s historic first Olympic gold medal in cross-country skiing [P] Nordic Focus](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Diggins-Randall-Games-BG5B6525-copy-525x399.jpg)

There wasn’t a dry eye in the American camp at Pyeongchang 2018, as the dream of achieving this incredible milestone marked a long journey by so many athletes, along with coaches, families, supporters and fans who all shared that dream and believed. Time will tell the full impact of this historic gold on generations to come. For now, the future of American cross-country skiing has never looked brighter!

![National camp action [P]...](https://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Duluth-4-2019-08-08-at-10.46.51-AM-300x246.png)

![Matt Liebsch on the CXC Elite Team [P] CXC...](https://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Matt-Liebsch-CXC.2-525x700.4-300x267.jpg)

![Dan LaBlanc [P]...](https://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Dan-LaBlanc-img_1855.3.jpg)

![Kikkan Randall (l) and Jessie Diggins with their Olympic gold medals [P] Sarah Brunson/USSA](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Randall-Diggins-Medals-FERN9156-copy-525x465.jpg)

![Legendary Martha Rockwell [P] Hall Collection](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Martha-Rockwell-copy-525x754.jpg)

![Alison Owen at the Junior XC Ski Nationals at Mt. Alyeska, Alaska in March 1969 [P] Owen Collection](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Alison-at-Junior-Nationals-Mt-Alyeska-1967-or-1968-copy-525x403.jpg)

![Training camp with head coach Marty Hall circa 1968 [P] Hall Collection](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Training-Camp-with-Marty-Hall-about-1968-copy-525x422.jpg)

![First U.S. women’s Nordic World Championship Team in 1970 [P] Hall Collection](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/First-World-Championship-US-Womens-Team-1970-DOC007.2-copy-525x422.jpg)

![U.S. women’s XC Ski team at the 2002 Olympic Games in Salt Lake City [P] Randall Collection](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/2002-W-Olympic-Team-copy-525x394.jpg)

![Judy Rabinowitz at the 1984 Olympics in Sarajevo, Yugoslavia [P] Rabinowitz Collection](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Judy-Rabinowitz-IMG_0039-copy-525x700.jpg)

![Sue Long at the 1985 Nordic World Championships in Seefeld, Austria [P] Hall Collection](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Sue-Long-Wemyss-1985-World-Championships-Relay-copy-525x352.jpg)

![Liz Stephen [P] Peter Graves file photo](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/Stephen-DSCN0278.2.jpg)