“Teo is the No. 1 priority. This is the first thing I think about when waking up or when any opportunity comes up. Being a mom comes first. When I stopped skiing, I didn’t really need to pursue anything more. I didn’t have the same kind of aspirational career goals many other people probably do,” says Beckie Scott. “I knew I wanted a child. I was really looking forward to this. Teo was really wanted, and Justin and I were prepared to make the lifestyle change for him. Teo fit right in.”

Something I’ve always admired are your pursuits outside skiing. You’ve been one to use your position as a recognizable athlete for the betterment of society. One of the first organizations you aligned yourself with was UNICEF. How did this come about?

Beckie Scott: I’d always cared about what was going on around the world. I think this is an influence from my parents. They are very aware and conscious of our place in the world — environmentally, socially.

It was the fall of 2001. The U.S. had just invaded Afghanistan. On the television, I saw this huge humanitarian crisis unfold. This really bothered me. I was really quite upset. As a team, we had just received our gear for the year. We were at a training camp, cooking for ourselves. We had bags and bags of food around. We felt we had so much. And here we are, seeing these images of people who had nothing. This contrast bothered me to the point of deciding to donate my prize money that year to UNICEF and trying to get as many others in the North American racing community to do the same. UNICEF is an agency helping the most vulnerable of all — the kids and the women, but mostly the kids who are the innocent victims in this kind of thing.

UNICEF got wind of what we were doing. The Salt Lake City Olympics were later that year. After I won the medal and got some notoriety, UNICEF asked me if I’d come on board as a special representative, a kind of ambassador for Canada. I said, ‘Yes’ [smiles] immediately. This was something close to my heart. Apart from skiing, this was the other realm I thought most about, that I wanted to be a part of. When they asked me to be an ambassador to their causes, they said, ‘If you ever want to see UNICEF in the field, if you ever want to visit projects, just say the word and we’ll build it into one of our projects.’ This was quite a fortunate door to have open. That year, I went to Burkina Faso in West Africa as part of their girl’s education campaign. After that, I joined the Right to Play movement.

Was it successful? Did people rally behind this cause?

BS: I think so. Many racers donated their SuperTour winnings, though it isn’t that much money, as you know [laughs]. In the end, we raised money for a genuine cause. But it was the simple gesture of awareness, as much as anything, that resonated so much with UNICEF and the ski community.

After Salt Lake, you went on a UNICEF field visit to Burkina Faso in Africa. Did participating like this help you as a ski racer?

BS: I think it helps keep the balance right. Going to Africa really helped me understand another world, another level of that people live at. To realize this, to see this, really put things in perspective — we don’t have much to complain about here. At times when I might be feeling negative or sorry for myself, I’d think back on these African experiences and I couldn’t stay in that mood very long.

The field visits also gave me another sense of purpose, which I was really looking for. When I took that break from sport, part of that was a feeling that I needed to look around for something other than skiing to keep me occupied, to keep me interested. I needed another avenue outside of skiing to focus my attention on.

Did this set up some of the work you’re doing now?

BS: Yes, totally. You know, this is one of the main reasons I came back. I spent days thinking about my reasons for coming back, what I wanted to do. One of the biggest reasons for continuing, apart from knowing I had more in me, was the knowledge that with increased success and notoriety, you get a platform. From that, I can spread the word, I can educate and I can draw attention to different causes and promote them.

I donated the money I won from my silver in Torino to a cause. This gave me another sense of purpose as well, in training and in the harder moments — to do something for kids.

You gave your Torino race bonuses to Right to Play that year, but didn’t tell anybody.

BS: I had a contract with Haywood Securities, a kind of victory schedule. The amount of money I won from my silver medal I donated. This idea of helping out a cause I believed in deeply was motivating, for sure. At the same time, when I stepped up to the start line, I was focused on executing the perfect race and getting this performance out of me. But this other motivation was certainly in the back of my mind.

You’re still connected to sport through the IOC [International Olympic Committee) athlete council and your work with Right to Play, which had limited involvement at the Vancouver 2010 Games. Can you tell us about that?

BS: Yes, that’s true. Right to Play was not officially in the Olympic Village, and didn’t have a partnership with the Vancouver Organizing Committee [VANOC]. This was over a sponsorship conflict and VANOC’s ultimate decision to bar Right to Play from participating in the Olympics as an official partner. It was disappointing how this unfolded.

How can an athlete who wants to be part of the Right to Play movement keep this alive?

BS: This is a very good question. The first is just spread the word — word of mouth. Talk about Right to Play when the opportunity presents itself in the media. Talk about a cause you support. Just showing your support — in any way this manifests itself — is most important.

Our athletes are our most important vehicle for advocacy, support and fundraising. Right to Play wasn’t inside the Village. But we were there and definitely had something for our athletes to show their support.

At the 2006 Torino Olympics, your peers elected you to an eight-year term on the IOC Advisory Council as the voice of the Olympians. How has this responsibility/opportunity been for you?

BS: It’s interesting. It’s eye-opening, for sure. I didn’t know exactly what to expect when elected. It seemed like a big deal at the time, and being an IOC member certainly has its perks [laughs]. But it also has a lot of responsibility. There’s a lot of travel and meetings and different kinds of official duties. So far, I enjoy it. It’s been very educational learning what goes on in the other side of sport.

When I think of IOC or FIS [International Ski Federation], I can’t help but think of an older-gentlemen’s club from Oslo or Monaco or St. Moritz. For all the empowering and democratizing power of athletics, there is a serious lack of gender equality in working in sports. I can’t name one woman serviceworker on the World Cup. I’d venture this trend is present in all levels of sport, but at the international level, there’s an absolute lack of women.

It’s really obvious how male-heavy coaching and support, even administration, is in sport; and in skiing in particular. It’s hard to say, but I think women bring a balance into a situation. There is gender balance on the start sheet, so I feel there should be some representation in the working aspect of the sport. At the same time, it’s a really hard lifestyle, really tough and demanding. Many women choose to have families, and after they retire from ski racing don’t want to do the travel that’s required. It’s a dilemma for sure. But I agree. There needs to be more women.

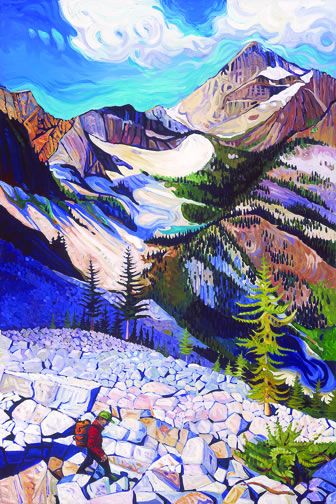

![“Liberty Bell” - The mountains are still the same. The route to the top isn't. [P] seanmccabestudio.com](http://skitrax.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/Liberty-Bell-copy.jpg) Since you’ve been a member, your biggest IOC decision has to be the Guatemala City vote where Sochi, Russia won the bid for the 2014 Winter Olympics. You were part of the evaluation committee. What went into this decision?

Since you’ve been a member, your biggest IOC decision has to be the Guatemala City vote where Sochi, Russia won the bid for the 2014 Winter Olympics. You were part of the evaluation committee. What went into this decision?

BS: I was part of an evaluation commission made up of hand-picked people from all different areas of expertise: lawyers, financial experts, transportation experts. Sixteen people were part of the commission. I was the only athlete and one of only three IOC members. The rest were individual professionals, respected as experts in their fields of study.

We traveled to all three cities: Sochi, Russia; Salzburg, Austria; and PeongChang, South Korea. Afterward, we went back to Lausanne, Switzerland for a focused week of preparing the report that we submitted to all the 112 IOC members in Guatemala City.

This report was a fairly lengthy and comprehensive overview about the three cities — to determine, in our opinion, which city was most capable of hosting the 2010 Olympics.

The IOC adopted this 16-person evaluation commission to cut down on corruption with previous Olympic bids, which came to light before the 2002 Olympic Games in Salt Lake, right?

BS: Yes. This is done to avoid all the bribery. So they say.

Can you tell me about this? I heard the IOC-commissioned report had Sochi, Russia as the bottom of the three bids.

BS: Sochi was not the strongest bid [long pause], according to the evaluation commission. I think if you read the evaluation commission report you would see that Sochi was not the strongest bid . . . [pause]

. . . in some respects.

I heard Vladimir Putin, the Russian President at the time, came down to Guatemala City to express his support for Sochi’s bid.

BS: He did.

Did this play any part in the swaying of the IOC members?

BS: [Laughs and laughs.] You know, who knows? I can only speculate. I was not approached in any way. Anything I heard is just secondhand speculation and hearsay. Every president and prime minister of the final-candidate cities came to Guatemala City. It just so happens that Putin is the most well-known. It’s really hard to know the external factors that went into influencing the voting, apart from the commission report.

Were you a little disappointed with the outcome?

BS: It surprised me a little.

One final question: where were you when Oddvar Bra broke his pole?

BS: Ooh, that’s a hard one. When was that? The 1982 World Championships in Oslo, right? I was eight years old. I don’t know. No. No, wait a minute. I was at a Vermillion Jackrabbit Jamboree.

Thank you for your time and insight, Beckie.

BS: Thank you.

Return to Part 3.